Thanks for reading or listening! You can show your support for my work by liking and sharing, buying me a coffee, or subscribing!

U.S. President Donald Trump recently threatened to impose tariffs on countries aligned with BRICS — the acronym given to a bloc of countries committed to economic and political cooperation. Its original members are Brazil, Russia, India, and China, who were later joined by South Africa. Hence the acronym. In the past few years, several other countries have joined the organization as well.

Why might Trump care about BRICS or wish to keep other countries from aligning with it? The answer is simple. BRICS, if not explicitly, implicitly presents itself as a counter to a Western-led, particularly American-led, economic and strategic international order. It made headlines not too many months ago for talks about developing a new currency that would allow its members to escape their dependence on the U.S. dollar for conducting international trade and finance among themselves.

Let’s put aside the question of whether deterring BRICS and dissuading other countries from joining is the right move. Reasonable people disagree, and I’ll confess that this issue is a bit out of my depth. Instead, I want to consider whether the strategy of using tariffs to achieve this goal has any bite.

I’ve written before about using tariffs to gain leverage over other countries, and a clear pattern emerges from the data: the U.S. has much less leverage than many assume. So color me skeptical that threatening tariffs on BRICS or adjacent countries will be an efficient strategy for curtailing unwanted behavior.

But just to be sure, I turned to the Correlates of War International Trade Dataset (4.0). This is an easy to access dataset for me in my software, but it also has the advantage of having dyadic detail about imports and exports which many other publicly available data do not provide. The term “dyad” is just a term international relations scholars use to refer to a pair of countries. Dyadic trade data, by extension, is data on trade taking place within a particular country pair, like the U.S. and China.

The one downside with using this data is that it stops in 2014. There are ways I could get dyadic trade data for more recent years, but those methods require some extra effort that I unfortunately didn’t have the time to implement for this post. That’s no big deal though, because relative trade values are a somewhat slow moving phenomenon.

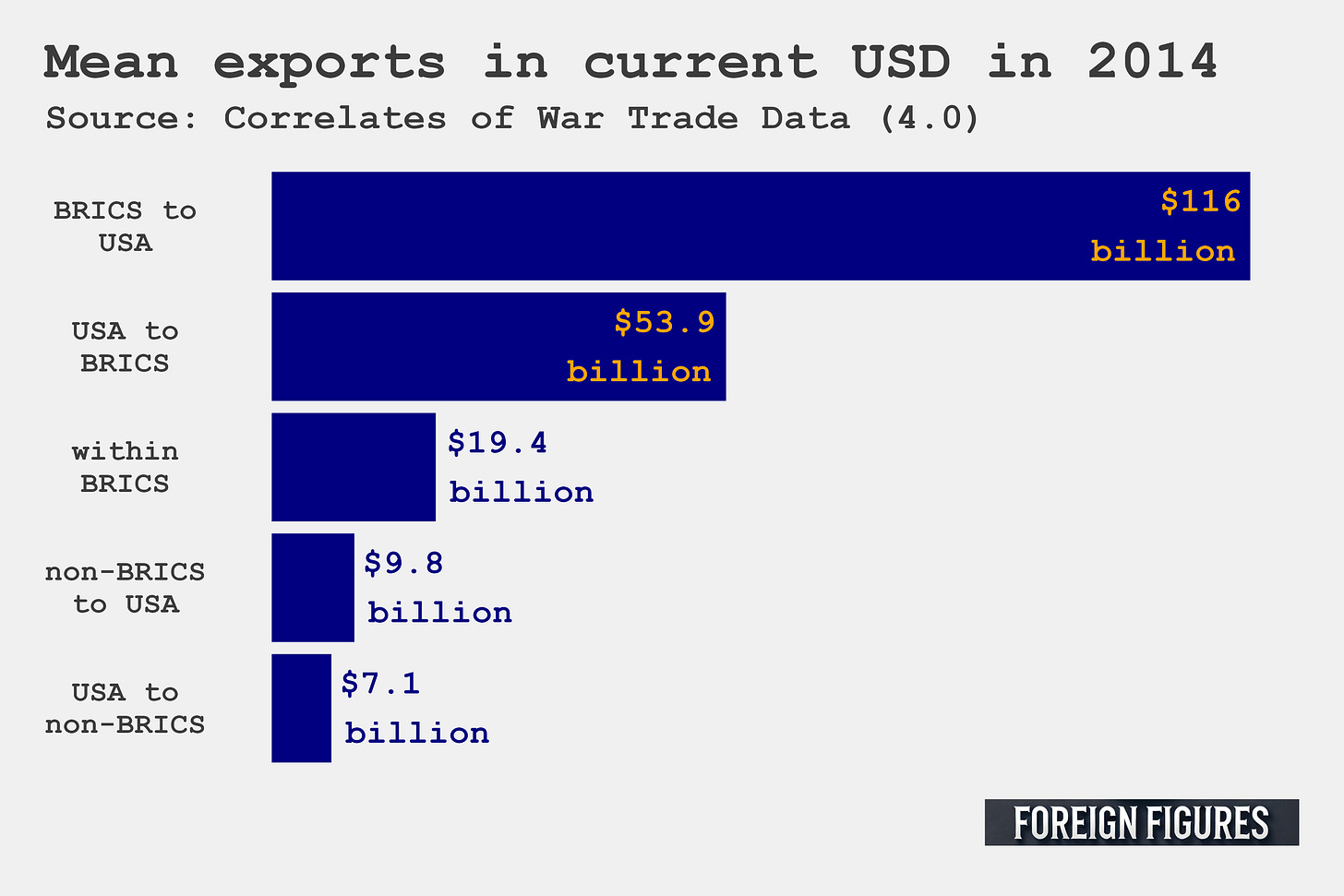

Alright, so what did I find? I first decided to break the down down by different groupings of countries and then summarize average exports between countries within each grouping. Specifically, I looked at exports from BRICS countries to the U.S. and vice versa, exports among BRICS members, exports from non-BRICS countries to the U.S. and exports from the U.S. to non-BRICS countries. I’m using the last year in the data, 2014, and I’m only including the five original members of BRICS in the grouping — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — because only these countries were members of the organization in that year.

You can see what I found in the figure below. I calculated average exports by grouping in billions of U.S. dollars and ordered them from highest to lowest. Starting with the highest, the average BRICS country exported $116 billion worth of goods and services to the U.S. in 2014. The U.S. exported $53.9 billion worth of goods and services to the average BRICS member. This is more than the average rate of exports within BRICS itself, which totaled $19.4 billion. Non-BRICS exports to the U.S. averaged only $9.8 billion, and U.S. exports to non-BRICS members averaged $7.1 billion.

You can clearly see that the U.S. and BRICS are more economically interconnected on average than the typical BRICS member is with its fellows. You can also see that there’s a definite trade imbalance — BRICS members on average export much more to the U.S. than the U.S. exports to the average BRICS member. But interestingly, the U.S. exports more on average to BRICS than the average BRICS member exports to other BRICS members. The U.S. also has little leverage by way of tariffs outside of BRICS countries for Trump's threat to impose tariffs on countries that would align with BRICS to have any bite. If anyone is going to be disproportionately hurt by U.S. tariffs, it’s one of the five original members of BRICS.

The economic toll of U.S. tariffs wouldn’t be felt uniformly by BRICS members, however. This much is plain to see in the next figure. For each of the five original members, I visualized total exports to the U.S. in billions of dollars as of 2014 and ordered them from highest to lowest. No surprise, China is at the top of the list, and there’s a lot of sunshine between it and the next country. In 2014, China exported $472.5 billion worth of goods and services to the U.S. India exported a fraction as much: $45.2 billion. It’s followed by Brazil who exported $30.3 billion, Russia who exported $23.7 billion, and South Africa who exported $8.3 billion worth of goods and services to the U.S.

The main takeaway for me is that tariff actions against BRICS are, practically speaking, tariffs directed at China. I wonder if this is connected to why China’s president, Xi Jinping, opted not to attend the recent BRICS summit in Rio de Janeiro which prompted Trump’s tariff threat to begin with.

While that might be a bit of stretch, it is true that China depends on access to the U.S. economy much more than the other members of BRICS. That also means that China is the pressure point the U.S. should prioritize if it wants to influence the organization and any other countries in its orbit. I’d be surprised if the general tariff threat Trump issued meets with success.

Code to replicate the analysis in this post can be found here.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, you can show your support by liking and sharing, buying me a coffee, or subscribing!